Story by Ella Slade

While only a 15-minute walk from the city center, the Griffeuille, one of Arles’ three quartiers populaires, resembles an entirely different city. As you approach from downtown, the Roman architecture and tourist-target boutiques fade into clusters of large, uniform housing projects.

Many people from these housing projects never go to the city center and vice versa, according to Fanny Petit, the coordinator of La Collective, a non-profit association in Arles that provides social and psychological services for women. “It’s like there is a frontier, an invisible frontier.”

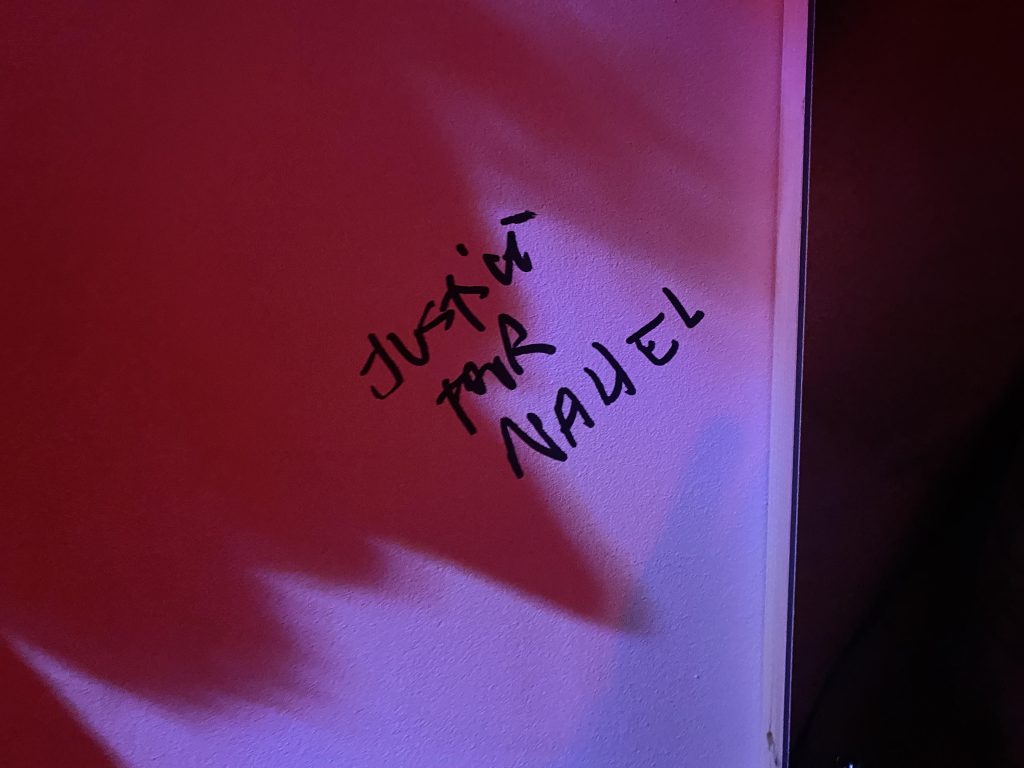

Recent events have shined a spotlight on those living in France’s quartiers populaires. On June 27, in Nanterre, a town in the western suburbs of Paris, 17-year-old Nahel M. was fatally shot in the chest by police, for driving off during a traffic check. The recent death of the teenager, who neighbors said was from a family of Algerian origin, triggered rioting and clashes with police around Paris and other communities throughout France.

In Arles, the reality is complex, leaving both urban and suburban communities with conflicting feelings of solidarity and estrangement. While the Griffeuille may not seem attractive to tourists, it is rich with diversity and home to a close-knit community, said Zachariah Yazidi, a resident of the Griffeuille, who compared himself to a local mail carrier. “We all know each other, we’re like a big family.

Quartiers populaires are categorized based on household income, communities where the median income is equal to, or less than, 60% of the national median wage (1,800€/month). The people who live in these communities are two times more likely to be immigrants than the national average and three times more likely to be unemployed, according to the Institut Montaigne.

A similar, but not interchangeable, term used is banlieue, meaning a set of administratively autonomous neighborhoods that surround an urban center.

Although it is the largest city in France by land area, Arles has a relatively small population of around 50,000 inhabitants.

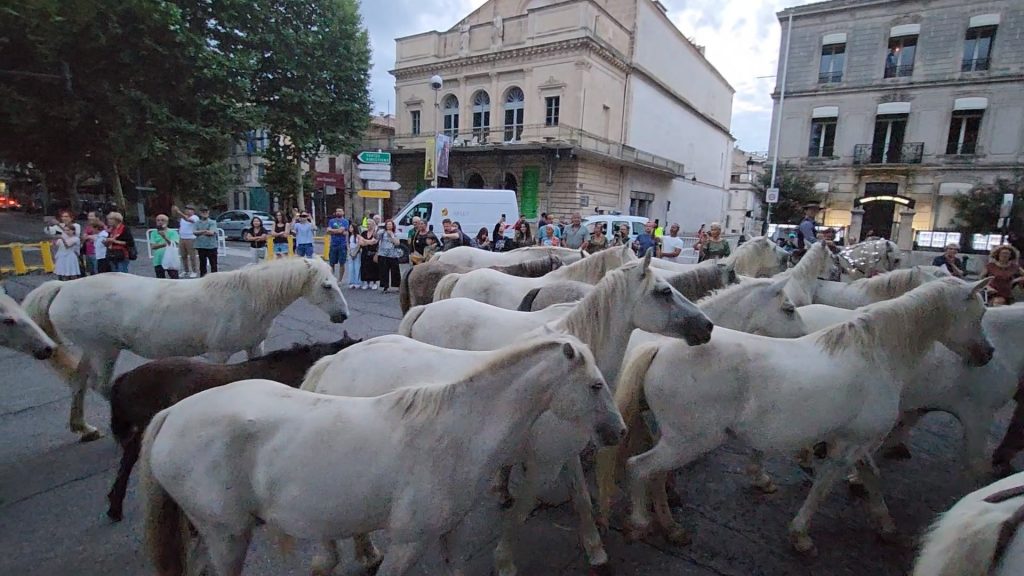

While riots broke out even in many small French towns, protesters assembled peacefully June 30 in Arles’ Place de la République.

Victor Parodi, who lives in Arles and will attend the University of Paul Valery in the fall, said he thinks that since Arles is a fairly small city, it does not host much social activism.

“You can see right away when you go to the biggest cities like Lyon, Marseille, Paris. This is where there is the most movement, and where there has been the most revolt and break-up,” Parodi said. “For example, I went to Marseille today. The riots were still two weeks ago and there were dozens of stores with the windows that were totally broken, stores that were looted, that were broken, stolen from.”

“It is also not necessarily in small towns where we will see these riots. The purpose of a riot is to see it everywhere, and in small towns people won’t necessarily see them,” said Samuel Lacassin, a recent graduate of Lycée Louis Pasquet in Arles.

The assembly in Arles included three audio broadcasts of testimonies from Nahel’s family, as well as other victims of civil rights violations and police brutality.

“There were 200 people [present], which is not enormous, but it’s consequential for the city of Arles, and there were 50 to 70 young people who came from the banlieue,” said Camille, an organizer of the assembly in Arles who spoke to The Arles Project on the condition of using a pseudonym. “Normally, in these political activist gatherings, most people are White and from the center of town.”

According to Camille, many who attended the assembly in Arles were social activists who have demonstrated together in the past.

Throughout the assembly, those in attendance were given time to speak and pose questions to law enforcement officials who were present.

“They immediately asked simple questions about their feelings,” Camille said. “A young boy, who is 11, talked about racism that he already knows, as he is a victim of racism at this age, which is very young. He asked the policeman, ‘Why do you arrest only Arabic and Black people, and why do you control them?’”

The officers, who stood on the periphery of the assembly, did not respond. A spokesperson for the Arles bureau of the national police told The Arles Project no one was available to comment by press time.

According to Camille, even a simple gathering in homage to Nahel and to denounce police racism is considered a threat to government officials in France. The problem is not just the racism of individual officers, Camille said. “It’s the laws around it, and how to live with systemic racism in the states and with the police in particular.”

“In places like the banlieue, where they’re not investing a lot of money and energy into making life better for these people, giving them more work opportunities, and giving them more education opportunities, obviously, there’s going to be economic difficulties,” said Sydney Firsching, an Arles-based intern at SOS Racisme, an organization which aims to combat discrimination and promote community cooperation. “All crime is a result of economic difficulties, really, in most cases, in many communities.”

Police stop teenagers in the Paris banlieue sometimes multiple times per day, she said.

That’s similar to the reality experienced by Cosmo Arnold, who also recently graduated from Lycée Louis Pasquet in Arles.

“Just the difference between how you interact with the police, for example, between the center of town and [the fashionable neighborhood] La Roquette, is two different worlds,” Arnold said. “I mean, they won’t do a thing if you’re in town, [but] they will chase you if you do a single bad thing outside of town, not even that far away.”

How can the cycle of poverty, over policing and violence end? “I think it [starts] by taking a step back and realizing how abnormal it is to have a police force that’s defending the state and the interests of a few over everyone else,” Arnold said. “And it’s all about not normalizing it. It’s by normalizing it, that it becomes more prevalent.”

Yazidi agrees. “As I explained to you, we are like a big family, and that’s why France is rising up. If someone killed someone in your family, someone you know, [you] would rise. At some point, people need to shout to be listened to by the government.”